“And Yeshua/Jesus stretched out His hand and touched him, saying, ‘I will; be clean” (Matt. 8:3; cf. 8:1-4).

Matthew records that when Yeshua descended from the mountain after the great sermon, the crowds who listened, followed Him. Jewish readers would immediately recognize the significance of this moment. Like Moses descending Mount Sinai with the Torah, Jesus comes down from the mountain carrying authoritative teaching about the Kingdom of Heaven. The crowds are astonished, not only by His words, but by the authority with which He interprets, teaches and embodies Torah itself (Jn. 1:14).

The first encounter that follows is unexpected. A man afflicted with leprosy, צָרַעַת /tzara’at, approaches Him.

In Jewish understanding of the time, tzara’at was not just a skin disease. As detailed in Leviticus 13–14, and later discussed extensively in the Mishnah tractate Nega’im, it represented a state of ritual impurity (tumah) that resulted in social and spiritual separation. The afflicted person was examined by a כֹּהֵן/kohen (priest), declared unclean, and sent outside the camp. He was forbidden from normal human contact, required to announce his uncleanness when walking or being approached by others (Lev. 13:45), and barred from Temple worship.

This was not punishment, but protection of holiness. Later rabbis understood leprosy to be the result of gossip, the effects of which spread rapidly in a community, destroying reputations and families. The Torah preserves the sanctity of the Lord’s dwelling among His people. This affliction was to lead the gossip to repentance, and ultimately restoration. Yet, the separation reality for the leper was devastating, cut off from family, synagogue, and sacrifice. He became, in every sense, an outcast.

Still, the man comes; and he broke religious and cultural boundaries to do so. He passes through the crowds to approach Jesus.

He kneels before Yeshua and says, “Lord, if You are willing, You can make me clean” (Matt. 8:2). This is a profoundly Jewish expression of faith. The man affirms Yeshua’s authority while submitting himself to God’s will. In rabbinic thought, healing always flows from the Lord’s compassion (rachamim), not entitlement. The question is not whether Jesus is able, but whether He is willing to act now.

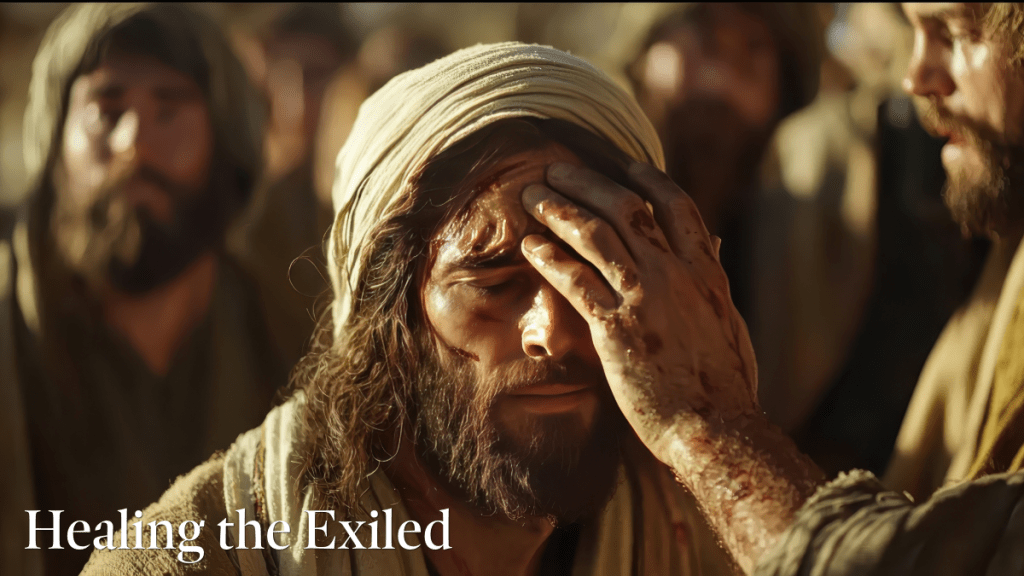

What follows is nothing short of shocking, “Jesus stretched out His hand and touched him.”

According to halakhic expectation, contact with a leper would render one ritually impure. Yet, Yeshua’s touch does not transmit impurity; instead, it transmits purity. In Jewish thought holiness is active, not fragile. As later rabbinic teaching affirms, the honor of human dignity (kavod habriot) can override certain restrictions when compassion/mercy is at stake. Here, Yeshua reveals that the Lord’s holiness does not recoil from human brokenness. Rather, it confronts it and restores it.

Before the man is cleansed, he is touched. This is critical. The healing is not just physical; it is relational. Yeshua restores the man’s humanity before restoring his status. Then He speaks: “I am willing. Be cleansed.” Immediately, the tzara’at/leprosy leaves him. The miracle echoes prophetic expectations of the Messianic age, when, as Isaiah foretold, the afflicted would be healed and the excluded restored (Isa. 35). Jesus recognized him, heard him, and healed him.

Still, Yeshua does not dismiss the Torah or the Temple. Instead, He says, “Go, show yourself to the priest and offer the gift that Moses commanded, as a witness to them” (Matt. 8:4). This instruction anchors the miracle firmly within the Word of God and expected practice. Leviticus 14 describes a detailed process for a cleansed leper: inspection by a kohen, offerings, and restoration to the community. Yeshua honors this process, affirming the ongoing authority of God’s commandments (cf. Matt. 5:17).

And He calls this a witness. A witness to the priests, and to the Temple leadership. Even to Israel itself. The witness is this: God is moving again among His people, because is among them (Jn. 1:10-11, 14). Cleansing is happening outside the expected channels, yet never apart from God’s Torah. This man, once exiled, now walks toward the Temple, but not defiled, he is restored.

This moment proclaims that the Kingdom of Heaven is not theoretical, it is not just a system of rules and regulation, it is faith in action according to His Word. It is faith reaches the margins. It touches the untouchable. It heals without abolishing God’s order. This miracle calls religious leaders to recognize that the Holy One of Israel is once again at work.

When Messiah descends the mountain, the first sign of the Kingdom is not judgment, but mercy. And the first testimony of His faithfulness is written on the restored body of a man whom no one else would or could touch, until the Holy One of Israel stretched out His hand.

This passage reminds us that Messiah meets us not at our strongest, but at our most excluded and isolated places. He touches what others avoid. He restores without dismantling God’s order; and He turns the healing of one outcast into a testimony for an entire generation, even all generations. When Yeshua descends the mountain, the Kingdom came with Him, and it reaches first for the ones no one else will touch.

Maranatha. Shalom.